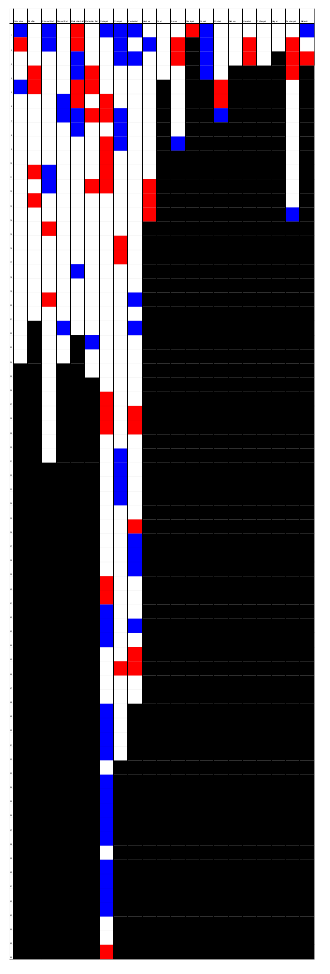

I made another haftarah info visualization! This time, red squares are haftarot we have covered, blue squares are haftarot we haven’t covered, white squares are non-haftarot, and black squares are not chapters of Tanach.

What should be plain from this image is that we still have a long way to go to cover all haftarot. Furthermore, if you’re expecting to learn all the prophets from the haftarot, you’re going to miss a lot. Zephaniah, Chagai, and Nachum don’t even get one… In any case, this week we get to see Michah!

Context

Michah is one of the Twelve Minor Prophets. He prophesied about both Yisrael and Yehudah during the reigns of Yotam, Achaz, and Chizkiyah, kings of Yehudah. Yotam was a good king but didn’t end the de-centralized bamah worship. Achaz was evil and practiced idolatry. Chizkiyahu was one of the best kings, even ending the bamah worship. Michah has 7 chapters.

- In 1-3, he mostly condemns the leaders and predicts their doom and downfall.

- In 4-5, he predicts a future redemption for Israel and the world, including destruction of the sinners.

- In 6-7:13, he describes G-d’s accusation of the people’s sins and details their crimes.

- In 7:14-20, Michah returns to the positive, predicting reconciliation between G-d and his people.

So the first half of our haftarah is one of Michah’s positive predictions, and the second half is an accusation of the people.

Overview

[5:6-8] Michah compares Israel to dew (for its independence from man) and a lion (for its dominance).

[5:9-14] G-d describes His future destruction of evil and idolatry.

[6:1-5] G-d testifies in front of the mountains to Israel’s perfidy despite His generosity.

[6:6-8] “How do I please G-d? Sacrifices? My child?” The response: justice, goodness, modesty.

“Like droplets on grass”

Torah readers will immediately identify the image used in verse 5:6 as a reference to the song of Ha’azinu. The verse reads as follows:

ו וְהָיָה שְׁאֵרִית יַעֲקֹב, בְּקֶרֶב עַמִּים רַבִּים,

כְּטַל מֵאֵת ה’, כִּרְבִיבִים עֲלֵי-עֵשֶׂב–

אֲשֶׁר לֹא-יְקַוֶּה לְאִישׁ, וְלֹא יְיַחֵל לִבְנֵי אָדָם. {פ}

6 The remnant of Jacob shall be in the midst of many peoples

as dew from G-d as droplets on the grass

which do not look to any man nor place their hopes in humankind.

The corresponding verse from Haazinu is Devarim 32:2 —

ב יַעֲרֹף כַּמָּטָר לִקְחִי, תִּזַּל כַּטַּל אִמְרָתִי,

כִּשְׂעִירִם עֲלֵי-דֶשֶׁא, וְכִרְבִיבִים עֲלֵי-עֵשֶׂב.

2 Let my lesson come down like rain, my speech distill as the dew;

like showers on young growth and like droplets on the grass.

The precise words “droplets on the grass” are repeated in both locations. However, despite using the same phrase, the navi throws the metaphor in an entirely different direction. [I’m sure there’s a literary term for this technique, where you subvert a standard metaphor to say something new, but my Google-fu was not up to the task of finding it.]

In Haazinu, the image of droplets on the grass is meant to express a life-giving beneficial teaching that enriches the grass receiving it. In the analogy, Moshe representing G-d is the giver of rain/dew, the Torah is the water, and the Jewish people are the grass. They are living organisms with all of the needs and challenges that accompany life. Moshe encourages the people to obey G-d and not rebel once they have settled down: he teaches them what it takes to survive and thrive.

In Michah, the droplets are the Jewish people themselves. Michah underlines a very particular property of rain: rain is not dependent on man. This is true, but rain isn’t really dependent on anything. Rain has no impulses, no needs, no tendencies. What is the use of the dew/rain analogy, when it applies just as easily to anything inanimate?

Perhaps, Michah is inviting us to compare this image with the image from Devarim. Here, just as in Devarim, G-d is still the giver of water, but the Jewish people are no longer the beneficiaries of G-d, they are the emissaries, the carriers of the Torah. Michah sees his audience in this period of time as being open to serving as the proverbial “light unto the nations.” This prophecy may have been delivered in the era of Chizkiyah, for example, when the people turned towards righteousness, but they still had to worry about the invasion of Assyria and the other political and military woes of the day.

Michah takes the classic image of dew and says that his audience will exceed the audience of Moshe Rabbeinu. Moshe’s audience drank of the Torah. Michah’s audience will carry the Torah to the world unencumbered by the oppression and violence that plauged them then.

“Remember what Balak king of Moav plotted”

The haftarah takes a sharp turn at verse 5:9. After spending three verses on positive predictions for Israel, the prophet shifts to negative predictions. In chapter 6 verses 1-5, G-d is presenting a case against Israel. The content of that accusation? That G-d has done no wrong and only good to Israel, so the people should be more grateful. In verse 3, G-d challenges the people:

ג עַמִּי מֶה-עָשִׂיתִי לְךָ, וּמָה הֶלְאֵתִיךָ: עֲנֵה בִי.

3 My nation, what have I done to you And what hardship have I caused you? Testify against me!

G-d presents three exhibits for evidence: 1. I brought you out of Egypt. 2. I sent Moshe, Aharon, and Miriam as leaders. 3. Remember what Balak wanted to do and how Bil’am responded to him. This is the most obvious connection between the parsha and the haftarah. But it’s not immediately clear why this event is relevant to this chapter of Michah. G-d performed any number of great kindnesses for the Israelites during their years in the desert! See Shmot through Devarim for examples, or Psalms 105 & 106 for a poetic retelling.

One feasible response is that the prophet wanted to mention an instance where G-d had saved them from an evil end. If that were the case, why not mention the miraculous victory over Amalek or Sichon & Og? In those cases, the Israelites knew about how grateful they needed to be to G-d.

Perhaps, the point of citing the example of Balak and Bil’am is that based on the previous verse, the Israelite may respond “Fine, Hashem redeemed us from Egypt, but then He delegated leadership to Moshe, Aharon and Miriam. G-d may help me from time to time, but He does not ‘walk with me.’” I apologize for invoking this cliche, but this Israelite may look at the lone set of footprints on the beach and think he’s alone. By mentioning Bil’am, the prophet says “that’s when G-d was carrying you.” Or more analogously, that’s when G-d was standing off to the side and making sure the shark didn’t eat you.

This idea may also inform the last verse of the haftarah:

ח הִגִּיד לְךָ אָדָם, מַה-טּוֹב; וּמָה-ה’ דּוֹרֵשׁ מִמְּךָ,

כִּי אִם-עֲשׂוֹת מִשְׁפָּט וְאַהֲבַת חֶסֶד,

וְהַצְנֵעַ לֶכֶת, עִם-אֱלֹקיךָ.

8 He has told you, O man what is good, and what Hashem requires from you:

Only to do justice and love goodnes,

And to walk modestly with your G-d.

Lest you think that your wanderings through the desert were out of G-d’s presence, remember that G-d is by your side. This also helps explain why we should stay modest — we can’t take credit for our successes, because G-d is aiding us.

Shabbat Shalom! Let the dewdrops of rest re-energize you for the coming week!

Leave a comment